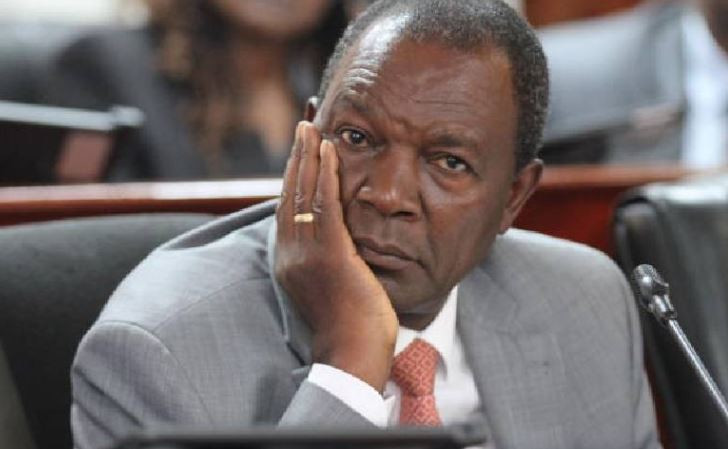

Treasury CS Njuguna Ndung’u delivered the Sh3.9 trillion 2024/25 Financial Year Budget Statement on June 13. Due to economic challenges, the budget had been revised downwards from a previous figure of Sh4.2 trillion. Kenyans are up in arms against the government for instituting tax measures that further raid their already constricted household budgets.

Politicians from both sides of the aisle have not made things any better by cherry picking contentious issues in the budget such as the motor vehicle circulation tax, and blowing them out of proportion. Thus, a cloud of uncertainty has been created over the Finance Bill 2024/25. Public Finance 101 gives an operational definition of tax as a price that society must be prepared to pay for its transformation.

The Constitution of Kenya 2010 provides a framework for a social contract between Kenyans and their governors. The mandate that is ingrained in the social contract requires those who govern to provide public goods to the citizens.

On their part, the citizens must pay taxes to the state to facilitate provision of services. Hence, the dictum of “no taxation without representation.”

The question that faces Ndung’u is not whether to tax Kenyans to underwrite provision of public goods, but rather how to tax them. Kenyans can choose either to willingly pay a little more taxes at present or pay much more unwillingly at a future date.

Let me explain. The government has both recurrent and development expenditures to underwrite from taxes and other revenues. There are only four sources of revenue to the Treasury, namely, ordinary revenue (Income Tax, VAT, Customs Duty, Excise Duty); Appropriations-in-Aid (revenues raised by government ministries and departments from their own sources, including court fines, eCitizen, etc); domestic borrowing (Treasury Bills and Bonds, and other sovereign debt instruments); and external funding for budgetary support.

These sources of revenue must be balanced in a way that ensures fiscal stability. Fiscal stability creates a good level of certainty in the economy that encourages investments as economic agents are able to make long term decisions.

To ensure financial independence and sovereignty, governments try to rely more on domestic revenue sources, and reduce external borrowing to the very minimum. In fact, the Mwai Kibaki administration achieved above 95 per cent self-reliance in its first five years.

A responsible government should ensure that external borrowing is maintained at below 10 per cent of ordinary revenue. Kenya currently finds itself in a very difficult situation where for every Sh10 raised in ordinary revenue, about Sh6.1 goes towards external debt servicing.

This leaves a paltry amount of only Sh3.9 to meet domestic debt obligations and service delivery to citizens, including education, health, physical infrastructure, water and sanitation, food security, national security, among others.

The government can hardly raise enough revenues from the current sources to effectively meet its recurrent and development expenditure obligations. An obvious consequence of inadequate provision of public goods is a less conducive environment for the private sector to commit their capital in the economy to create more jobs.

In essence, if Kenyans don’t pay enough taxes, the capacity of the government to attract new investments and retain the existing levels capital in the economy will be grossly undermined.

Therefore, it behooves Kenyans to actively join in the conversation about the options available to CS Ndung’u for raising additional revenues. It is not enough to complain that taxes are too high without providing viable alternatives. External borrowing for budgetary support, aside from undermining a country’s sovereignty, represents economic hemorrhage as debt repayment takes priority over all other expenditure.

The Kenyan situation with respect to external borrowing is not very pleasant as the Debt to GDP ratio is already way past 50 per cent, making additional borrowing to be very expensive due to loan syndication.

A syndicated loan is one that is contributed to by several loaning institutions as a way of risk diversification. So, the external option is already too expensive for the economy. Ndung’u must now look inwards for budgetary support. Local debt is much better than external borrowing because once redeemed, it goes back into the economy to increase liquidity, reduce interest rates and shore up investments and capital accumulation.

Undoubtedly, the cheapest source of government revenue is taxation. The Kenya Revenue Authority has done an excellent job in the last three quarters by growing revenue by 15 per cent. However, this is hardly enough to underwrite the agenda of the Kenya Kwanza regime. The government must therefore, explore additional sources of ordinary revenue in order to protect citizens from further accumulation of external debts.

Kenya needs to exercise stringent fiscal discipline. In this regard, KRA should be supported to strengthen its capacity for revenue mobilisation. This will call for continuous modernization of the institution’s internal processes to facilitate decision making, addressing governance concerns, professionalising human resources, and creating formidable partnerships with stakeholders.

Finally, the elephant in the room should be confronted. There is excessive wastage in government. Every so often the Auditor General raises issues about extravagance, money that cannot be accounted for, increasing impunity and lethargy. The result is that inordinate amounts of revenue goes to waste. Ndung’u needs to crack the whip and bring Kenya back on a responsible fiscal track.

The writer teaches at the Technical University of Kenya, and is a former Chief Manager at KRA

vincent.ongore@tukenya.ac.ke