Jazz is broad and has variety. Jazz is a music form generally performed with an individual’s own imaginations in a variety of configurations that suit their impulses. And with such components applied, some musical renderings instantly capture the listener’s attention with great impact.

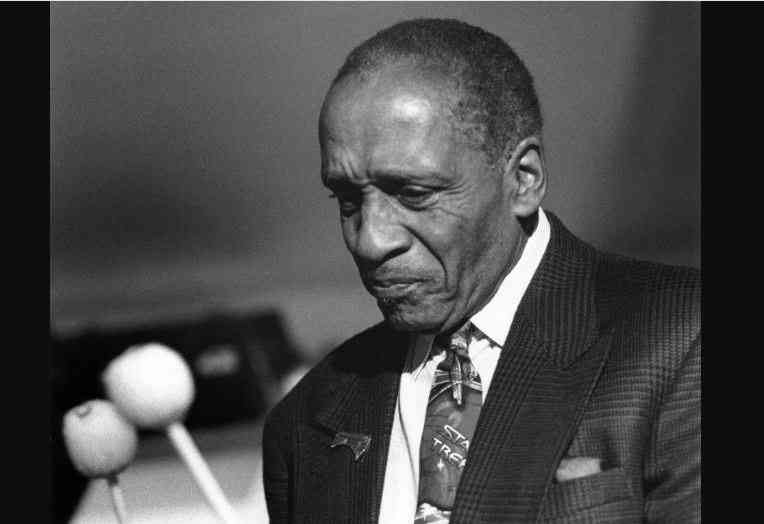

One such musician was the pioneer bebop vibraphone player Milt “Bags” Jackson, whose mastery of the idiom when it emerged in early 1940s was and still is legendary. He was a co-founder with pianist John Lewis of the Modern Jazz Quartet (MJQ) in 1952, after working with trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie. In MJQ, which lasted 22 years, he was also in the fabulous company of drummer Connie Kay, bassist Paul Chambers and pianist Hank Jones.

On his solo album, Statements, released in 1962, Jackson showcased his artistic flexibility on originals and standards, consisting of the blues and ballads, all rendered with a good measure of swing and improvisational ingenuity. Celebrated for his romantic charm on the vibraphone (offshoot of marimba), Bags stood-out as he showcased different elements from his earlier performances with MJQ, and also with the two bebop style innovators, Parker and Gillespie, in one of his most relaxed album offering.

Featured are six Jackson originals: the album title and opening track Statements, A Thrill from the Blues, Put Off, A Beautiful Romance, Blues for Juanita and Big George, while the standards are Kermit Goell-David Raksin’s Slowly, Duke Ellington’s Paris Blues and I Got it Bad That Ain’t Good, Sonnymoon for Two (Sonny Rollins), The Bad and the Beautiful (David Raksin), Gingerbread Boy (Jimmy Heath) and Anything I Do (Chester Conn-George Douglas). Some of the songs on the album were from a 1964 recording that featured pianist Tommy Flanagan and tenor saxophonist Jimmy Heath titled Jazz ‘n’ Samba.

Jackson abandoned his earlier laidback style familiar in MJQ and instead swung and improvised ebulliently on pieces such as Statements and A Thrill from the Blues, on which his improvisations come through loud and clear. Still, his vibraphone gets smoother with reflective and melancholic intonations in his lead lines and solos on Slowly, a tune with a yearning melody, and Paris Blues with terrific accompaniment by drummer Kay, bassist Chambers and pianist Jones. Jackson was a big fan of Duke Ellington, who composed it as the theme song for the film, Paris Blues.

The leader gets even more stimulated on The Bad and the Beautiful, on which he plays the vibraphone with thoroughly expressive lyricism. The quartet’s groove moves deeper into the blues mode with Jackson’s original A Thrill from the Blues, which the composer described as “just a straight blues.”

Milt Jackson was born on January 1, 1923, in Detroit, Michigan, and by 1945 was established as the pioneer bebop vibraphone player. His sessions with yet another jazz great Thelonius Monk showed him as one of the great interpreters of the distinctive and eccentric composer-pianist’s music, as featured on Monk’s Genius of Modern Music, I Mean You, and Criss Cross, among others.

In 1974, after 20 years with the Modern Jazz Quartet, with whom he released more than 45 albums, the vibraphonist decided to go solo. But in 1981, the MJQ members were persuaded to reunite to play at the Newport Jazz Festival.

Their return to the international festival circuit was highly celebrated. They were undiminished in form, content and performance; the quartet’s marvelous music stood the test of time.

Milt Jackson passed away on October 9, 1999, and has been described as a modern traditionalist whose playing went back to the most basic blues foundation, distilling decades of modern jazz.

His solos were superb, and there was a certain playful and energetic tone that bounced from his fluid vibes. He crafted so penetratingly personal a style that made him the most influential vibraphonist of his generation.

In his sunset years, he had stripped his style of excesses and instead focused on the emotional content of whatever he played.